A cat is confident one moment and the next is acting defensive or fearful. A normally friendly and happy cat is suddenly beating the crap out of a housemate. Kitty is obviously enjoying a good petting from head to tail, then BITE. What changed the dynamic?

Some people think you’re joking when you talk about cat stress, thinking of the domesticated indoor feline who sleeps 22 hours a day (really it’s right around 16, but that still seems like a lot), has someone else clean her toilet, and only has to worry that the pull-tabs work on all her cans of food.

And yet behavioral studies have, well, “stressed” the prevalence of feline “stress”, not only in observing and interpreting their behavior but in setting up their “household” with these things in mind.

Cats don’t experience the world as we do, so in order to understand we need to think like cats for a bit. Cats are very close to their original biology even though they are domesticated animals and have lived with humans for tens of thousands of years. They react to their indoor life through the eyes of a cat living outdoors without all the accouterments we give them, where they are not only predator but also prey to other animals, where ensuring their safety from predators and other dangers—just staying alive—is the most important thing on their agenda, food and reproduction coming after that.

This is what makes deciphering cats so difficult—when we’ve taken care of their safety we think they know they don’t have to look over their shoulders all through the day. But they are still compelled by biology to do just that because, living in nature, a good bit of their time is actually spent ensuring that their territory is safe, and monitoring it to ensure it stays that way, patrolling it, rubbing their faces on some things and scratching on others to leave their scent and physical marks for themselves and other passersby.

This routine is imprinted on their behavior, and they need to follow this daily pattern even inside your house. If one part of the routine is prevented or unavailable or changes, they feel the stress of a threat to their personal safety. And just like humans, one stressful thing can pile atop another, and another, and…where individually a cat could deal with each stressor, several at once can be overwhelming, and, just like humans, they have a little meltdown. Or a big one.

How did we not see it coming? We know that cats hide pain as a biological response to preserving their own safety—they also hide stress and fear for the same reason. You may never know these things are a problem until your cat starts up with some odd or destructive behavioral issues that seem to come out of nowhere without careful observation.

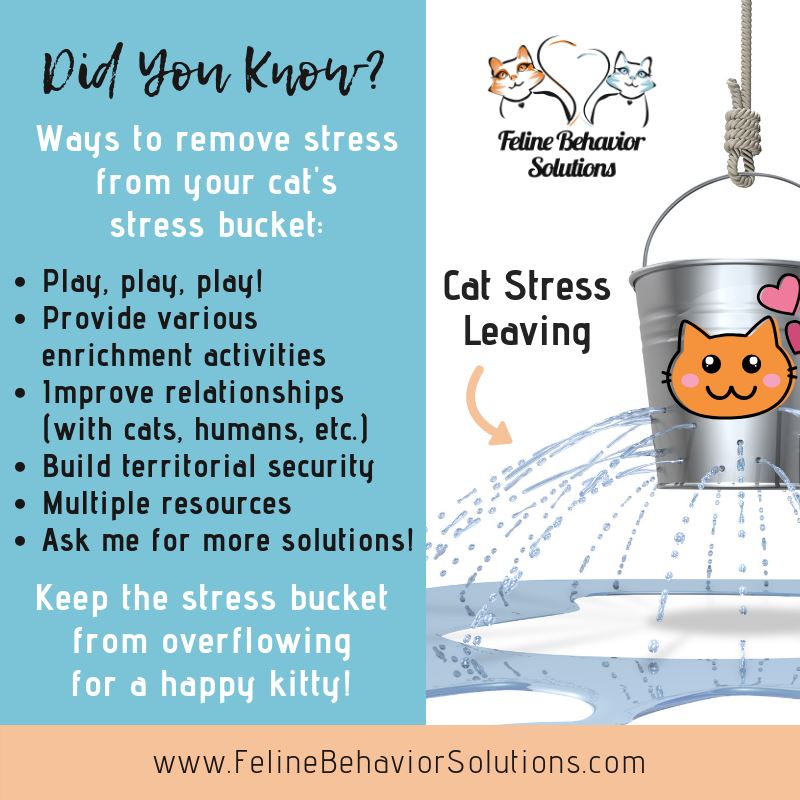

The sources of cats’ stress have been discovered and confirmed with behavioral studies of cats. Dr. Marci L. Koski, Certified Feline Behavior & Training Consultant and owner of Feline Behavior Solutions, described thinking about your cats as having a “stress bucket.” Stressful things can go into the bucket from various sources:

- boredom, inactivity

- relationships with other cats, animals, people

- territorial insecurity

- outdoor animals

- noise, foreign smells

- subpar litterbox setup

- resource competition

“When the stress bucket overflows, that’s when problems start cropping up,” says Dr. Koski. “You can let stress out of the bucket by turning down the faucet letting things in (correcting/reducing the stressors themselves) or turn on a spigot to let stress out (through play, etc.).”

She noted that the size of the stress bucket is variable for different cats – “older cats typically have smaller stress buckets, for example.” Not only can you try to remove some stressors, like changing the litterbox setup or blocking the view of outdoor animals, but you can also add to your cat’s day with fun things that help distract them from the stressful issue and, in time, help them adjust:

- play! play! play!

- provide various enrichment activities

- improve relationships (with cats, humans, etc.)

- build territorial security

- provide multiple resources

Don’t underestimate “boredom” as a stressor. A cat’s daily activities in nature, patrolling her territory, marking things with her scent and marks, includes climbing trees, visiting other cats and possibly even people, then the whole process of hunting for food—cats are actually very busy animals. They sleep many hours to help them rest after periods of intense activity. “Boredom” happens when nature tells them to do these things, but there is no opportunity to do so, and no opportunity to work off the energy the body provides to spend on that active time, and that’s when cats either eat too much, or get in trouble.

Matching up the best relief activity for the stress can take some tinkering, but it all starts with observation. Watch your cats closely at any time, not just when they have behavioral issues. Get a baseline on how they act when they are confident, and when they act out, start with looking at what is different about the situation.

- If they enjoyed two pets but bit you on the third, try petting them only twice, then stopping to tell them how much you love them before resuming.

- If two cats start having conflicts, where and when does it happen?

- Don’t set up areas or buy toys you think they will like, choose them by observing their own natural preferences.

And remember, they’re not just being jerks, there’s always a reason behind their behavior. If working to relieve stressors doesn’t work, a call to a certified cat behaviorist or a visit to the veterinarian is in order.